Written by Dr Paul Jamient, the astrophysicist turned diet guru. Across species, animals have different diets to match the differences in their digestive tracts. Humans ALSO have some variations, actually making interspecies dietary variations by up to 5% of food composition.

Paul's 90min youtube lecture is very good and I recommend it for people interested in a discussion of what foods are a human's makeup designed to process. Definitions of poison, how many research papers in the field are produced a year and how to sort through them, best sources of food. The way many problems are solved is by throwing the greatest minds at them - Paul has one such mind. I will get his book to review very soon.

Is There a Perfect Human Diet?

Filed under: Perfect Health Diet“All healthy persons are alike; each unhealthy person is unhealthy in his own way.”

If Tolstoy were a diet-and-health blogger, this might be how he would begin.

All healthy persons are alike

The composition of cells hasn’t changed much since the origin of complex multi-cellular life about 500 million years. Apart from water, the major components are fatty membranes and proteins. More than half the proteins are glycosylated – bonded to glucose-derived carbohydrates. These compounds – fats, proteins, and glucose – are the basic “macronutrients” needed by cells. In organisms, these cells are supported by an extracellular matrix composed of glycans and proteins; this matrix is mineralized in bones and teeth.Why do animal species differ in their nutritional needs? Actually, nutrient needs differ remarkably little across the animal kingdom. This is why animals comprise “food” for one another: the ingredients of all animals are the same, so one animal nourishes another.

It is also why breast milk varies little across all mammalian species: the composition of cow’s milk is not much different from the composition of lion milk, for instance – or human milk for that matter.

Human nutrient needs differ from those of other mammals chiefly by virtue of our larger brains, which are rich in omega-3 fats and require extra glucose for energy. But large brains only modestly tweak the needed macronutrients: compared to other mammals, an extra 10-15% of calories as glucose, and an extra 1% of calories as omega-3 fats, are more than sufficient to nourish a human.

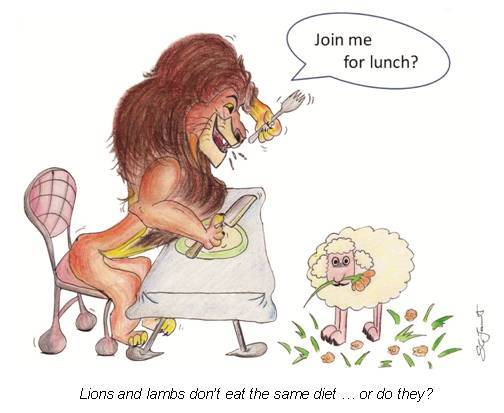

If all animals are alike in their nutrient needs, why are diets so different? Why don’t lions sup with lambs?

It turns out that what differs among the animals is the composition of the digestive tract. Animals have evolved digestive tracts and livers to transform diverse food inputs into the uniform set of nutrients that all need. Herbivores have foregut organs such as rumens or hindgut chambers for fermenting carbohydrates, turning them into fats and volatile acids that can be used to manufacture fats. Carnivores have livers capable of turning protein into glucose and fat.

When we look past the digestive tract at what nutrients are actually delivered to the body, all mammals obtain a remarkably similar set of nutrients. By calories, mammalian diets are always composed of a majority, typically 50-75%, of saturated and monounsaturated fats (including the short-chain fatty acids produced by fermentation of fiber); a mix of carbohydrates and protein, usually totaling around 25-40%; and a modest amount of polyunsaturated fat, typically less than 10%.

If diets differ because of digestive tract differences, we should expect the same pattern to recur in humans. All humans have the same nutrient needs, but our optimal food intake may vary if our digestive tracts differ.

In fact there is evidence for variations in digestive tract structure among human populations. Melissa McEwen has summarized evidence that Africans have slightly larger colons, suggesting a slightly more plant-focused evolutionary diet, and Europeans have slightly smaller colons, suggesting a more animal-focused evolutionary diet [1, 2].

Longer colons allow more fermentation of plant fiber, but they don’t dramatically change macronutrient ratios of the diet. Across human populations, the optimal human diet probably doesn’t vary in any macronutrient by more than 5% of energy or so.

So there is little support for a “blood type diet” or “metabolic type” with significantly different food needs. All healthy people can and should eat a similar diet – one that approximates to our body’s nutrient needs.

Each Unhealthy Person is Unhealthy in his Own Way

What are the causes of ill health? We believe there are three fundamental causes of ill health: malnutrition, toxins, and infectious pathogens.There are dozens of elemental nutrients – vitamins, minerals, and biological compounds – whose absence in the diet can impair health. Many thousands of toxins, totaling several grams in weight daily, enter the human body; as Bruce Ames and Lois Gold have shown [3], plants make a host of natural food toxins, and food storage and cooking create more. Finally, we are continually exposed to microbes; there are probably hundreds of pathogens capable of establishing human infections.

It doesn’t take a mathematician to see that there myriad possible combinations of malnutrition, poisoning, and infection. The causes of disease are legion; it’s no surprise that the manifestations are so various. The number of possible combinations of disease causes is more than the number of humans. To a first approximation, every disease is unique.

Each combination of causes will affect the optimal diet in a different way. People who are malnourished will benefit from getting more of the things they are malnourished in, and perhaps less of others which balance those – as reducing zinc may help someone who is copper deficient, or reducing omega-6 fats may help someone who is omega-3 deficient. People exposed to toxins may benefit from an extra dose of toxin-metabolizing nutrients. People with infections may benefit from diets which starve pathogens of needed nutrients, or which support immune function. People with gut dysbioses may benefit from removing or reducing whole classes of foods – starches, fructose, FODMAPs, fiber, even protein.

Infections can make a big difference in the optimal diet. Ketogenic diets, which starve the brain of glucose but feed it with small molecules derived from fats, are highly effective against bacterial infections of the central nervous system, since bacteria depend on glucose metabolism. But hepatitis B and C viruses can utilize the process of gluconeogenesis – manufacture of glucose from protein – for their own benefit, so people with hepatitis benefit from higher carb diets.

Other pathologies disrupt the ability to handle certain nutrients. Diabetes is characterized by an inability to secrete insulin, and diabetics usually benefit from low-carb diets. Migraines, like epilepsy, may be caused by genetic or other impairments to brain glucose metabolism, and can often be cured by ketogenic diets, as several of our readers have discovered.

With ill health, the optimal diet often changes. Sick people often have to tweak their diet, and the nature of the change varies with the nature of the pathology.

Diet Can Be a Diagnostic and Therapeutic Tool

Precisely for this reason, diet and nutrition have a valuable place in the healer’s arsenal. A sick person’s response to dietary changes can be informative about the nature of his pathology.For instance, ketogenic diets are therapeutic for bacterial and viral infections, but can feed protozoa, fungi, and worms (which have mitochondria and can metabolize ketones). Response to a ketogenic diet can help expose the nature of an infectious pathogen.

Because neurons are dependent on glucose or ketones for energy, any pathology which disrupts glucose utilization will cause neuronal starvation, and neurological and psychological distress, which can be relieved by provision of ketones. A well-designed, nourishing ketogenic diet may often ameliorate psychiatric and neurologic disorders.

Dietary tactics can help prevent as well as treat disease. For instance, fasting upregulates autophagy (“self-eating”), the cellular mechanism for recycling damaged or unnecessary components. But autophagy is a central part of the innate immune system; it is how cells destroy invading microbes. Intermittent fasting as a regular practice helps keep the body infection-free, and during intracellular infections refraining from food is often a helpful strategy.

For some pathogens, on the other hand, providing the immune system with plenty of food is usually a better strategy. “Feed a cold, starve a fever” – or is it the other way around? Your body will usually tell you what to do, suppressing or promoting hunger as needed.

Conclusion

There is no one diet that is perfect for everyone, but that is mainly because not everyone is healthy.Fortunately, healthy people are generally alike in their dietary requirements. We can identify a diet that is very good for nearly everyone, and can tweak that diet in various ways to help diagnose and heal diseases. That is the goal of our book, Perfect Health Diet, and of this blog.

References

[1] Katsarski M, Singh U. [Anatomical characteristics of the sigmoid intestine and their relationship to sigmoid volvulus among the population of Uganda and the city of Plovdiv, Bulgaria]. Khirurgiia (Sofiia). 1977;30(2):159-63. http://pmid.us/916568.[2] Madiba TE, Haffajee MR. Sigmoid colon morphology in the population groups of Durban, South Africa, with special reference to sigmoid volvulus. Clin Anat. 2011 May;24(4):441-53. http://pmid.us/21480385.

[3] Ames BN, Gold LS. Paracelsus to parascience: the environmental cancer distraction. Mutation Research 2000 Jan 17; 447(1):3-13. http://pmid.us/10686303.

No comments:

Post a Comment